WOMEN AT WAR

Women in the Civil War: Strength, Sacrifice, and Service

The American Civil War was not fought solely on battlefields—it was also waged in hospitals, factories, and homes. Women played vital roles in all these arenas, stepping into responsibilities that had long been denied to them. They served as nurses, worked in factories and arsenals, became Vivandières (a French word for women who are attached to military regiments as sutlers or canteen keepers), and even disguised themselves as soldiers. Others kept homes, farms, and businesses running in the absence of men. This exhibit highlights just a few stories of the resilience and courage of these women, who took bold steps in redefining their place in society.

Nursing and healthcare were among the most visible and significant contributions of women during the war. Thousands, including notable figures like Clara Barton, Dorothea Dix, and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, worked tirelessly to care for wounded soldiers. They endured long hours, unsanitary conditions, and societal restrictions that often kept them from fully participating in medical practice. Their dedication not only saved lives but also laid the foundation for the professionalization of nursing and opened doors for women in medicine.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

Yet not all women worked in hospitals. Many found employment in armories and factories, producing weapons, ammunition, uniforms, and other critical supplies. Though dangerous, these jobs offered higher wages than traditional domestic work and attracted entire families despite the risks. Their labor sustained the war effort and revealed a new economic role for women.

Some women defied all gender expectations by disguising themselves as men to enlist and fight. Soldiers like Sarah Edmonds, Frances Clayton, and Albert Cashier risked everything to serve their cause, blending into military ranks and proving themselves in combat.

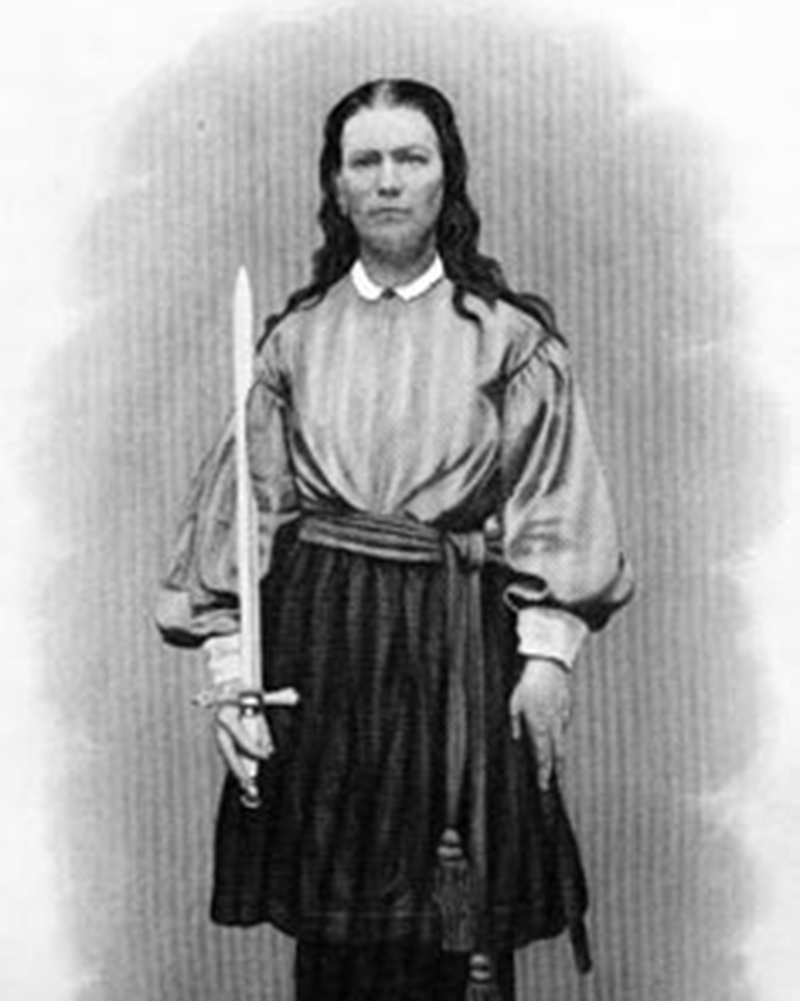

Frances Clayton — Also Known as Franies Clalin

Meanwhile, women on the home front carried immense burdens including maintaining farms, running businesses, raising children, and managing households without the support of husbands, fathers, or sons. Their perseverance and ingenuity helped hold the fabric of civilian life together in a nation at war.

The Civil War marked a turning point for American women. Their experiences proved their capacity to contribute far beyond traditional domestic roles. These wartime contributions empowered many to advocate for greater rights in the postwar years and helped lay the groundwork for the women’s suffrage movement. Their stories are not just side notes, they are essential chapters in the history of the Civil War.

Vivandèires

Vivandières, women who volunteered to travel with regiments to provide support to soldiers, first emerged in the French Army during the Crimean War. Though not trained for combat, these courageous women served as canteen bearers, cooks, nurses, laundresses, and providers of comforts such as alcohol and tobacco. Armed for protection, they played a significant role in both the Union and Confederate armies during the American Civil War. However, the most notable Vivandières served with the Union Army.

Sarah “Guardian Angel” Taylor

Serving in the 1st Tennessee Union Infantry with her stepfather, Taylor was known as the “Daughter of the Regiment.” Armed with a sword and pistols, she cheered troops in battle. Captured as a spy in 1862, newspapers reported she escaped with an aide’s help, but her fate remains unknown.

Spies Among Us

The American Civil War was not only fought in the open—but also in the shadows. Hidden beneath layers of secrecy, subterfuge, and coded messages were the daring efforts of women who risked everything to gather intelligence and pass it across enemy lines. These women, often dismissed by society as harmless or incapable of espionage, used the very perceptions of their time to their advantage. They smuggled documents in hoop skirts, memorized troop movements, and operated right under the noses of military commanders. Their quiet cunning helped shape battlefield outcomes and redirected the course of campaigns—yet their names are often left out of the broader narrative.

Elizabeth Van Lew

Elizabeth Van Lew was born on October 12, 1818, in Richmond, Virginia. In the 1840’s, her family owned as many as 21 African Americans. However, both she and her mother believed slavery was morally wrong, and they worked to secretly free some of their slaves. By the time the war broke out, she had become an abolitionist. She freed some of the people her family had enslaved and allowed others to live freely during the war.

After the Battle of Bull Run, Van Lew began visiting Union prisoners held in Richmond’s Libby Prison. She not only brought them aid and comfort but also helped several prisoners escape. When martial law was declared in Richmond in March 1862, she intensified her efforts and officially began working as a spy.

In 1863, Union General Benjamin Butler learned of Van Lew’s activities and recruited her for formal clandestine work. With the help of Unionist citizens in Richmond, Van Lew’s home became the center of a sophisticated underground spy network. One of her agents even secured a clerkship in the Confederate War Department, giving them direct access to valuable intelligence.

The intelligence gathered by her ring was passed on through Samuel Ruth’s spy network, which also conducted sabotage operations along the railroads from Fredericksburg to Petersburg. Colonel George Sharpe, head of intelligence for the Army of the Potomac, received the information and relayed it to Union generals.

After the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, General Ulysses S. Grant personally visited Van Lew’s home to thank her for her vital contributions to the Union cause. Throughout the war, she had exhausted her family’s fortune to support her espionage work and was left destitute by its end.

When Grant became President in 1869, he appointed Van Lew as Postmaster of Richmond in recognition of her sacrifices. She held the position for eight years, until the next administration declined to renew her appointment. Despite being shunned by many of her neighbors and former friends, she remained in Richmond.

Elizabeth Van Lew died in 1900, impoverished and ostracized by her community, even being referred to in the press as “Crazy Lew”. While she was hailed as a hero in the North, she continued to be seen as a traitor in the South.

Maria "Belle" Boyd

Maria Isabella “Belle” Boyd was just 17 years old when she gained fame as a spy for the Confederacy during the Civil War, earning several nicknames, including “La Belle Rebelle” and the “Secesh Cleopatra.”

In 1861, her hometown of Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), fell to Union troops. Soon after, a Union soldier confronted Boyd and her mother about a Confederate flag displayed on their home. When the soldier insulted her mother, Belle drew a pistol and fatally shot him. An investigation cleared her of wrongdoing, and shortly after, she began her career as a Confederate spy.

On May 23, 1862, as General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s troops approached Union-occupied Front Royal, Virginia, Belle spied on Union officers and raced to inform Confederate forces about their positions. Her efforts helped secure a Confederate victory.

Belle often visited Union camps, charming officers to gather information that she passed along to Confederate commanders. Eventually, she caught the attention of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. She was arrested and imprisoned in Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., spending a month behind bars before being deported to the Confederacy. In total, she was arrested at least six times for her espionage activities, eventually fleeing to England.

After the war, Belle published her memoir, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison, and toured the country giving lectures about her wartime exploits. She died on June 11, 1900.

Pauline Cushman

Born in New Orleans to a Spanish father and French mother, Pauline Cushman was raised in the frontier town of Grand Rapids, Michigan. She eventually pursued a career in acting and found modest success on the stage. But her most dramatic role came not from the theater—it came during the American Civil War.

In 1863, while performing at a theater in Louisville, Kentucky, two paroled Confederate officers approached Pauline. They asked her to deliver a toast to Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy during her performance. Though initially appalled, she reported the proposal to the Union Provost Marshal. Rather than discouraging her, the officer advised her to go through with the toast—believing it could be a unique opportunity to gain access to Confederate sympathizers and gather intelligence.

On the night of the performance, the theater was filled with both Unionists and secessionists. When the moment came, Pauline stepped forward and boldly declared:

“Here’s to Jeff Davis, and the Southern Confederacy. May the South always maintain her honor, and her rights.”

The crowd erupted, some with outrage, others in applause. The toast cemented her cover as a loyal secessionist and earned her entry into Confederate circles. She was soon sent across Confederate lines, posing as a woman searching for her brother, a Confederate officer. All the while, she was secretly collecting valuable intelligence for the Union.

Eventually, Pauline was caught with incriminating drawings of Confederate fortifications. Arrested, tried, and convicted as a spy, she was sentenced to hang. However, before the execution could take place, she fell gravely ill in her prison cell. Then fate intervened—the Confederate Army retreated as Union forces advanced, and Pauline, too sick to be moved, was left behind. Union forces rescued her, and she made a swift recovery.

In recognition of her daring service, she was awarded the honorary title of Major of Cavalry. After the war, she spent years touring the country, sharing the thrilling story of her espionage work and survival behind enemy lines.

Rose O'Neal Greenhow

Maria Rosetta was born around 1815 in Montgomery County, Maryland. She went by the name of Rose, and moved to Washington when she was around 13, and quickly became fascinated with the city’s social scene. In 1835, she married Dr. Robert Greenhow, and became a prominent socialite in Washington, D.C., cultivating friendships with influential political figures. Robert died in 1854, leaving her with four children. However, her inheritance and pension from her husband helped her to sustain her socialite lifestyle.

As the Civil War approached, Rose became a fervent supporter of secession and began spying for the Confederacy. In early 1861, Confederate Captain Thomas Jordan recruited her to lead a pro-Southern spy network in Washington. Utilizing her social connections and charm, she gathered valuable intelligence from high-ranking Union officers and politicians. Her most notable contribution was providing Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard with information about Union General Irvin McDowell’s planned advance on Manassas, Virginia. Beauregard credited her dispatches with influencing his request for reinforcements, which contributed to the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run.

On August 23, 1861, United States authorities arrested Rose for espionage. Even under house arrest and later imprisonment, she continued her intelligence activities, smuggling messages to the Confederacy. In 1862, she was released and exiled to the South, where she was celebrated as a hero. The following year, the Confederate government sent her to Europe to garner support for their cause. While abroad, she published her memoir, “My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington,” detailing her experiences.

In 1864, Rose attempted to return to the Confederacy aboard the blockade runner Condor. Fearing capture after the vessel ran aground near Wilmington, North Carolina, she insisted on being rowed ashore. The small boat capsized in rough waters, and Rose drowned, weighed down by approximately $2,000 in gold coins sewn into her clothing that was intended for the Confederate cause. She was buried with military honors in Wilmington’s Oakdale Cemetery.

Influential Women of the Civil War

Not all contributions to the Civil War effort were made on battlefields or behind enemy lines—some came through influence, advocacy, and the power of presence. Several women stood at the crossroads of politics, personal tragedy, and social change, shaping public perception and pressing for justice in their own distinct ways.

Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln was the First Lady of the United States from 1861 to 1865. She was born on December 13, 1818, into a prominent slaveholding family in Lexington, Kentucky. Well educated for a woman of her time, she developed a strong interest in reading, literature, and politics from a young age.

In 1832, Mary’s older sister Elizabeth married and moved to Springfield, Illinois. Mary began visiting her there in 1837 and eventually settled in the city. It was in Springfield that she met Abraham Lincoln. Despite a brief broken engagement, the two married on November 4, 1842.

Mary strongly supported Abraham’s political career. Her intelligence, ambition, and political insight were assets as he rose in prominence. Lincoln faced electoral setbacks during his career including losing several races for Congress the Senate, although he served a term in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. In 1860, he was elected the 16th president of the United States, and the Lincolns moved to Washington, D.C.

Mary’s family was sharply divided by the Civil War. Of her 13 siblings, several supported the Confederacy, and some even served in the Confederate Army. Because of her family’s Southern ties, many Northerners suspected her of Confederate sympathies. Despite these accusations, Mary was a firm supporter of the Union cause and an opponent of slavery. She also aided the Contraband Relief Association, an organization that aided formerly enslaved people who had fled to Union-held territory.

The Lincolns had four sons: Robert, Edward (Eddie), William (Willie), and Thomas (Tad). Edward died in 1850 at the age of four, likely from tuberculosis. The three surviving sons moved to Washington with their parents. In February 1862, tragedy struck again when Willie died of typhoid fever at age 11. His death deeply affected both Abraham and Mary and cast a shadow over the rest of their time in the White House.

On April 14, 1865, just days after the Civil War ended, Abraham and Mary went for a carriage ride through Washington. Reflecting on the hardships they had endured, Lincoln remarked, “We must both be more cheerful in the future—between the war and the loss of our darling Willie, we have both been very miserable.” That evening, they attended a play at Ford’s Theatre, where Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth. He died the following morning, April 15, 1865.

Mary never recovered from the trauma of her husband’s assassination. She wore mourning clothes for the rest of her life and became increasingly involved in spiritualism, attending séances in the hope of contacting her deceased loved ones. In 1871, her youngest son, Tad, died at age 18 from tuberculosis. Her mental health deteriorated, and in 1875, her only surviving son, Robert, had her briefly institutionalized at a private asylum in Illinois. Upon her release, she lived quietly with her sister Elizabeth in Springfield.

Mary Todd Lincoln died on July 16, 1882, at the age of 63, from a stroke. She is buried beside her husband and three of their children at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

Varina Davis

Varina Davis was born on May 7, 1826, in Louisiana and raised in Natchez, Mississippi. Her father, William Howell, was the son of a former governor of New Jersey, while her mother, Margaret Kempe, hailed from Virginia. Educated in Philadelphia, Varina developed strong ties to the North and maintained correspondence with Northern acquaintances throughout her life. She was well-educated for a woman of her time, intellectually curious, and considered had progressive qualities that sometimes clashed with her future husband’s more traditional beliefs.

Varina met Jefferson Davis at the home of his older brother, Joseph Davis. Although she fell in love with him, she often felt overshadowed by his devotion to his first wife, Sarah Knox Taylor, who had died young. The Howell family, having lost most of their family wealth due to bad investments and overspending, was financially dependent on the Davis family, which Varina found embarrassing. However, her move to Washington, D.C. after Jefferson’s election in 1846 brought her joy. She later described her years in the capital as the happiest of her life.

After the establishment of the Confederate States of America and the election of her husband as its first President in 1861, Varina reluctantly assumed the role of First Lady. Though she fulfilled her duties, she was ambivalent about the war and even expressed empathy for enslaved people, views that alienated many in the South. Her critics attacked her not only for her politics but also for her appearance, with some cruelly suggesting her olive complexion indicated mixed racial heritage. Varina’s personal life was marked by deep sorrow, as most of her children died in infancy or early adulthood, including five-year-old Joseph who died after falling from a balcony in Executive Masion in Richmond in 1864.

Following the Civil War, Varina struggled with poverty and marital strain, made worse by her husband’s extramarital affair. Though they never divorced, the couple spent much of their later years apart. After Jefferson Davis’s death in 1889, Varina moved to New York City, where she began writing for Joseph and Kate Pulitzer’s newspaper. She was embraced by many Northerners but continued to face criticism from the South, where she and others like her were disparagingly labeled “Confederate carpetbaggers.”

Varina Davis died of pneumonia in 1906 at the age of 80. Her body was transported to Richmond, Virginia, where she was buried with full honors beside her husband and daughter Winnie at Hollywood Cemetery.

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was an abolitionist, a woman’s rights advocate, and social reformer. Born Isabella Baumfree in 1797 to enslaved parents in Ulster County, New York, she endured forced labor and physical abuse throughout her early life. In 1826, she liberated herself and her daughter, one year before slavery was officially abolished in New York State.

After gaining her freedom, she experienced a powerful religious awakening. She became a Methodist and changed her name to Sojourner Truth to reflect her mission: to travel and share her spiritual and moral convictions. Truth became a compelling voice in the abolitionist movement, challenging societal norms and insisting that all women, especially Black women, deserved equal rights.

In May 1851, she delivered her most famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?”, in Akron, Ohio. Though the popular version of the speech was transcribed in a Southern dialect, Truth had grown-up speaking Dutch as her first language in upstate New York. In her address, she boldly confronted the contradictions in how society viewed women of different races, dismantling stereotypes and expectations.

During the Civil War, Truth recruited Black men to serve in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and worked tirelessly to improve conditions for formerly enslaved African Americans. In 1864, she met with President Abraham Lincoln to discuss the treatment of freed people.

Truth continued her advocacy for racial and gender equality long after the war. She passed away on November 26, 1883, at the age of 86, leaving behind a legacy of courage, conviction, and justice.

https://www.thesojournertruthproject.com/compare-the-speeches/